- Home

- Johnny Mercer

We Were Warriors Page 3

We Were Warriors Read online

Page 3

I made some extremely good friends at Eastbourne. I was still very different to them, and rather ashamedly begrudged their ‘normality’, but on the whole they didn’t judge me for my ‘different’ home life, and I didn’t end up in too many scraps with the posh kids. There were four of us in particular – Olly, Dan, Mike and me – who always seemed to end up in the same sports teams and at each other’s houses (except mine) when time allowed. From sixteen onwards we were also trying to get into pubs and drink, pretending to be the adults we most certainly were not.

I completed my GCSEs and then A Levels with lower than average results – ten GCSEs grade A–C and three A Levels C–E. I almost completed my Gold Duke of Edinburgh Award (my mother had already bought her hat for the palace) but got caught taking a taxi when I’d had enough on one of the practice yomps and was thrown off the scheme. I wasn’t too upset; by then I was starting to pay a little more attention to females and had mainly used the expeditions as a chance to chat to girls in a captive environment – their tent on a rainy night – and to get away from bloody music practice.

I remember the dreaded day when my A Level results came through. I had been working a series of jobs and saved some money to go abroad after I’d finished the exams, so I was away from home when the results came through. I don’t know why I was shocked by how poorly I had done, but I still was. My wonderful sister Naomi kept ringing up UCAS clearing, trying to get me a university place that I didn’t really want. In the end, I called off the chase. I was done with full-time education.

It wasn’t that I was lazy – I was a bloody hard worker – I just found concentrating on one thing particularly difficult when I had such mammoth internal battles going on. I had no idea what I was going to do with my life. Only when I was physically exhausted did I seem to manage a modicum of internal peace, when my mind would stop ticking over. I needed to try and get to grips with it all. There was very little awareness about ‘mental health’ in those days. I just felt like I was mad.

3

I got my first job at the age of fourteen, as a paperboy. The early starts, coupled with the criminal pay, were only ameliorated by the chance to flick through the latest Playboy with the other lads in the newsagent. We’d have about five minutes before we’d be sent on our way to deliver them through people’s letterboxes, together with the Kent and East Sussex Courier. It was always awkward when I recognized the name from chapel.

Being a paperboy was followed by working as a waiter and slops man on the washing up machines at the Spa Hotel in Tunbridge Wells. Being a waiter was harder work than I hoped for, but I made up for it with regular sit-ins inside the walk-in refrigerator, tasting the delicious yoghurt or wolfing down a cold croissant because I hadn’t got up early enough to eat breakfast.

When I was eighteen, I progressed to Lighting Department Manager at a department store. I say I was the manager, but I didn’t manage anyone. What I did manage to do was get together with the head of the menswear department, who was a very attractive girl five years my senior. Unfortunately, she was also the girlfriend of a notorious hard man, who was quite upset when he found out. Overhearing a conversation between her and the regional manager in the store cafe, when he told her that being with me was ‘not good for her career’, was a low point.

Luckily, I found a more serious job through Olly from Eastbourne College, who had essentially became my surrogate brother as we went through our teens. His father owned a farm in Sussex, and I could stay there during school holidays, for as long as I wanted, in exchange for chores. I spent most of my summers there. Olly Pile overlooked the many oddities that I had developed in my childhood, and was still trying to shake off in my adolescence, even though I reckon they made me pretty hard work to hang around with. We spent long, hot summers driving illegally across the South Downs on his motorbikes or drinking ale for the first time, listening to Oasis and Blur. One thing I had to put up with was his family’s determination to drink milk straight from the cow, without any skimming or treatment. We often went shooting, with mixed results. I was no dead-eyed Dick, but Olly really struggled with a gun. I would often drive the truck right up next to a rabbit in the dead of night, only for Olly to shoot the wing mirror off. Awkward conversations at breakfast with his long-suffering father were the norm.

Somehow Olly managed to get us both a job in London through some rich uncle of his. We’d be working for a fund manager in Farringdon, and our role there was to answer the phone, do the admin for some of the fund’s products and try to start a career in finance.

We lived with one of Olly’s family friends just off the King’s Road. I passed the financial exams but found the rest of it mind-numbingly dull, and consequently messed around far too much in an attempt to escape my mental wrestles. By day, I looked at my fellow workers and was filled with sympathy that this was their lot in life – an office in London, the daily commute, a very small world. By night, I was drinking far too much in an effort to sleep, and being a dick in the process.

I spent the majority of my time trying to get with a girl who worked in the office, but had once been a dancer in one of those gentlemen’s establishments. I wore her down and eventually she taught me a thing or two. I always pitied my partners in those days; my nocturnal pseudo-religious behaviour meant they must have thought me very odd indeed. Her boyfriend was rather unhappy with me as well. Incidentally and rather ironically, he was also some sort of hard man from Essex. Looking back I’m not sure what sort of girls I was going after . . .

Before long, it was clear that spending far too much money, drinking a fair amount and chasing posh girls down the King’s Road, while trying to build a career in something that failed to hold my interest at all, was not enough for me.

My father, who had relaxed a great deal by now after many years of strict adherence, wanted me to join the military like my brothers. I agreed that this might be something I’d be interested in, but I certainly wasn’t set on it. While I wavered, he succeeded in getting me an interview with a retired General he knew through his work at the bank.

The General got the measure of me within a few minutes (it wasn’t hard), and told me he had a plan for me. He paid for me to spend two days in February with a couple of his old soldiers, who had left the Special Air Service to set up a civilian training and leadership company. The course was held in the woods not far from my family home. We dispensed with the teambuilding tasks and high-wire courses pretty early on, and spent much of the day and late into the night chatting.

They outlined how much they had enjoyed the military, and were very honest about why they left. They had achieved what they had wanted to as young men, and they carried the air of confident, self-assured professional and personal satisfaction that I longed for but found entirely missing in London. They had lived a boy’s dream – friends, the SAS, operations, war, holidays. And, crucially, they seemed stable and happy. I wanted that.

They made me feel that even I could join the Army, despite knowing so little about it. I should join a specialist unit, and then I could be the outdoors loner of my youth on exercise and operations but a ‘normal’ person in barracks – a perfect mix, it seemed to me.

I said I wanted to sign up as a soldier and do it ‘properly’. I didn’t really fancy being an officer. I didn’t want the responsibility, or the discomfort I’d already experienced at Eastbourne College of spending my time with much wealthier, and better educated and bred men than me.

But the two men told me not to be such a prick. If I was good enough I should be an officer – the Army needed good officers from all sorts of backgrounds – and who was I to judge where I best fitted in? I could, after all, spend all my time with the blokes if I wanted to. I didn’t have to become a moleskin-wearing, corduroy-jacketed wonder overnight.

I asked what was the most pressurized and demanding role in the Army. They suggested that controlling joint fires – meaning coordinating aviation, air, artillery and mortar fire – while people were being shot, w

as very testing. It came with a lot of pressure and responsibility. I would have to master multiple technical and communications skills and operate at the highest professional standards; mistakes killed people. And I would get to scrap with the enemy too. Apart from the last bit, I was sold.

I did some research and found the only unit of the Army that I thought ticked all of these boxes. In Plymouth, on the south coast, there was a specialist unit called 29 Commando Regiment, Royal Artillery. The mix of soldier and seamanship that my family history demanded was a bonus. You had to pass the notorious All Arms Commando Course to join them, and then work your way up through the guns and reconnaissance jobs before you could become a fires controller – the job I was after. Training would take a few years and I could build a career. What came after that, I would have to wait and see, but I would always be a Commando. I might have a wife and a family by the time I had finished, who knows? One thing was certain – Plymouth was a long way away from Sussex.

That was what I was really after, if I’m honest. A family of my own in my own part of the world, where I could stand on my own two feet and perhaps put the past behind me. Home still defined everything I did. I found Christmases extremely sad; epic fall-outs were inevitable as we all struggled to readjust to a changing family dynamic – parents and siblings alike.

The battleground in my mind had become debilitating, and interfered heavily in my daily life. I felt I had blown it: by attending Eastbourne College, I had been given academic opportunities that were beyond so many; I simply had not made enough of them. My fear of my parents was now replaced with an almost sympathetic view of them. Despite their shortcomings, they had worked hard to earn money to enable me to go to that school. I felt like an incredibly wasteful kid sometimes.

But it was out of my hands. I was unstable and unhappy, and I longed for some inner peace from the religious torment that engulfed me every time I went to bed. Despite slowly becoming an adult, I felt like a boy emotionally. I thought that I struggled inordinately due to some strange lack of robustness. I had moments – days even – when the battles would leave me. But they always returned. My self-esteem was affected enormously.

As I turned nineteen, I knew I had to leave all this stuff behind and re-shape myself before my mind was lost. The Army was for me.

I sat my Regular Commissions Board – the entrance exams for officer training – in 2000; for the first time I really wanted to pass something and perform to my capacity, rather than let my performance be shaped by my internal struggles.

Inevitably, I totally cocked it up. If one could simply leave one’s internal struggles behind at the flick of a switch, the world would be a very different place. I was shy around the other candidates – all these ‘hooray henrys’. I would have happily sat there and taken the piss out of them all day, but struggled to discuss the finer points of Field Marshal Slim’s principles of war. Insecure piss-takers were not really what the Army was looking for.

I felt like a bit of a fraud, and let it show. Having taken on some significant ‘timber’ during my time in London, I was painfully slow during the physical assessment. I went home convinced that for the first time I had had a lifeline hung out for me and I had thrown it away.

While I was at Westbury, where the RCB was based, I was told about a course for those who hadn’t failed the Board outright, but were generally considered ‘below par’. Those who passed it would win a place at Sandhurst. Called Rowallan Company, it was the sort of course around which countless legends brood and was designed to build character through leadership for those a bit rough around the edges. It was made for me.

By now I was living with my brother Keith in Lewes, Sussex which had a good rail link to get to London for my job with the fund manager in the City. Keith had given up his career as a naval aviator to earn some money and have some fun flying for Virgin Atlantic. And having fun he was. He would often take me on trips with him, but what we got up to cannot be committed to paper. Keith also introduced me to curry, and we had a cracking local pub, full of Sussex hippies. There we would while away the evenings, putting our piano skills to good use and singing old songs, updating them with ruder and ruder lyrics about hippies until we were inevitably asked to leave, laughing as we were booed out of the door. We did have an extraordinary fraternal bond, borne out of the shared experiences of our upbringing.

I remember the summer morning at Keith’s when I got my results letter from Westbury. The words on the posh paper were shouting out at me. I had scraped through with a ‘Rowallan Pass’. They even sent me a video of the course, showing some lads my age running around in rugby shirts carrying what looked like a telegraph pole. It seemed like fun. Life was a little bereft back then.

When I informed my father, to his credit he was adamant I should attend Rowallan. I wasn’t so sure, by now only half-committed to a potential career in the Army. Then something happened that changed the world profoundly, and cemented my decision to join up.

I returned early from working in London one day and flicked on the TV. It was 11 September 2001. I watched the first plane, and then the second, crash into the Twin Towers. Then the first tower fell. I saw a couple of jumpers – those faced by the agonizing choice between burning in the building or falling to their death. I was talking to Olly on the phone as the second tower came down.

If I’m being entirely honest, there wasn’t much nobility in my initial decision to join the Army. The idea of travelling the world, playing sport and getting away from home life was enough for me. However, in the immediate aftermath of 9/11 those motivations began to be rivalled by another; one that affected many that day, and that had affected generations before me in times of great national change.

I grew up with the IRA creating havoc in the UK and dominating our news agenda. Their victims were often unconnected to the province and wholly innocent of wrongdoing. On 9/11 a lot of those who died hadn’t even heard of Al Qaeda; many were Muslims. Dead for going to work.

The world could be a very dark place. Dark men with dark ambitions could only run amok if your average man like me stood by, and allowed this evil to spawn. I didn’t know much about being a Muslim, but I knew enough to understand that killing three thousand innocent people in New York on a bright September morning had nothing to do with it. These cowards didn’t believe in anything. It was all about power and selfish ambition trading on man’s inhumanity to man.

As I was maturing and relinquishing the bonds of home life, I started to develop a real need to stand up to those who preyed on the weak and the vulnerable in society, perhaps unsurprising given the way my siblings and I entered the real world after growing up in our family. Even now, when I think of those who took the piss out of us back then . . . I would like to meet them again.

So back then on that infamous day, and in my own way, I still wanted to fight back against what I was seeing, however desperately ill-equipped a messed-up young man like me may have been. I knew I wanted to contribute. Something was growing inside me – a combative spirit. I was beginning to feel like a bit of an animal – at my best when physically exhausted, when my mind would finally rest somewhat. I thought if I could learn to tame it I might become a good soldier.

These motivations propelled me forward in those few months before I did something life-changing like entering the Army, a time when everyone wants to change their mind.

The Royal Military Academy Sandhurst is the premier military academy in the world. My father drove me to the gates. By now I was very well-informed about the course I was about to undertake. It cost half a million pounds to run, produced very few officer candidates, and because of this low pass rate (six of forty-two on my intake) it was being discontinued. I was going to be ‘fortunate’ enough to be part of the final class. It was, as the training team would never let me forget, a ‘privilege’.

Dad and I were slightly early on 28 January 2002. We went and sat in the Camberley Marks and Spencer across the road for a cup of tea. I had never been to the

area before in my life. Through the academy’s gates we could see an imposing, palatial facade with some immaculately kept lawns running up to it.

The nausea was almost overwhelming. At twenty, I was a good seven years younger than the average age of people attending Sandhurst. I was considerably underqualified too – four out of five had degrees, and those that didn’t had a decent business background behind them, or had already entered the Army in the ranks and were now looking to commission.

My father, I think, saw himself as the general who never was. I distinctly remember part of our conversation over that M&S cup of tea.

‘What if I don’t like it, Dad? Lots of people don’t.’

‘You will like it, son.’

That was that.

4

It was cold that January afternoon when I arrived in A Block, Rowallan Company. The staff were very pleasant to our parents. However our parents were quickly shepherded out of the door at which point we were ordered out of our civilian clothes and into our uniform for the next three months – denim trousers, a rugby shirt, combat high boots and a 1958 pattern webbing belt with a black army-issue water bottle on it. We put our civilian clothing into a holdall, which was then locked away.

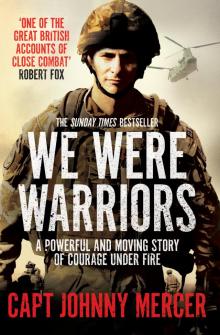

We Were Warriors

We Were Warriors